Atilla Shrugged

Act III - Scene II

The Cannibal Monk

Famine in the Age of Plenty

At a party at Prince Myshkin’s Villa in heaven. Talking and laughing. Ayn is dancing a triumphant jig alone to an old phonograph recording of a ‘Marionettes at Midnight’, pivoting her finger to the center of her head as she does pirouettes. She takes up a baton and pretends to conduct the orchestra, triumphantly.

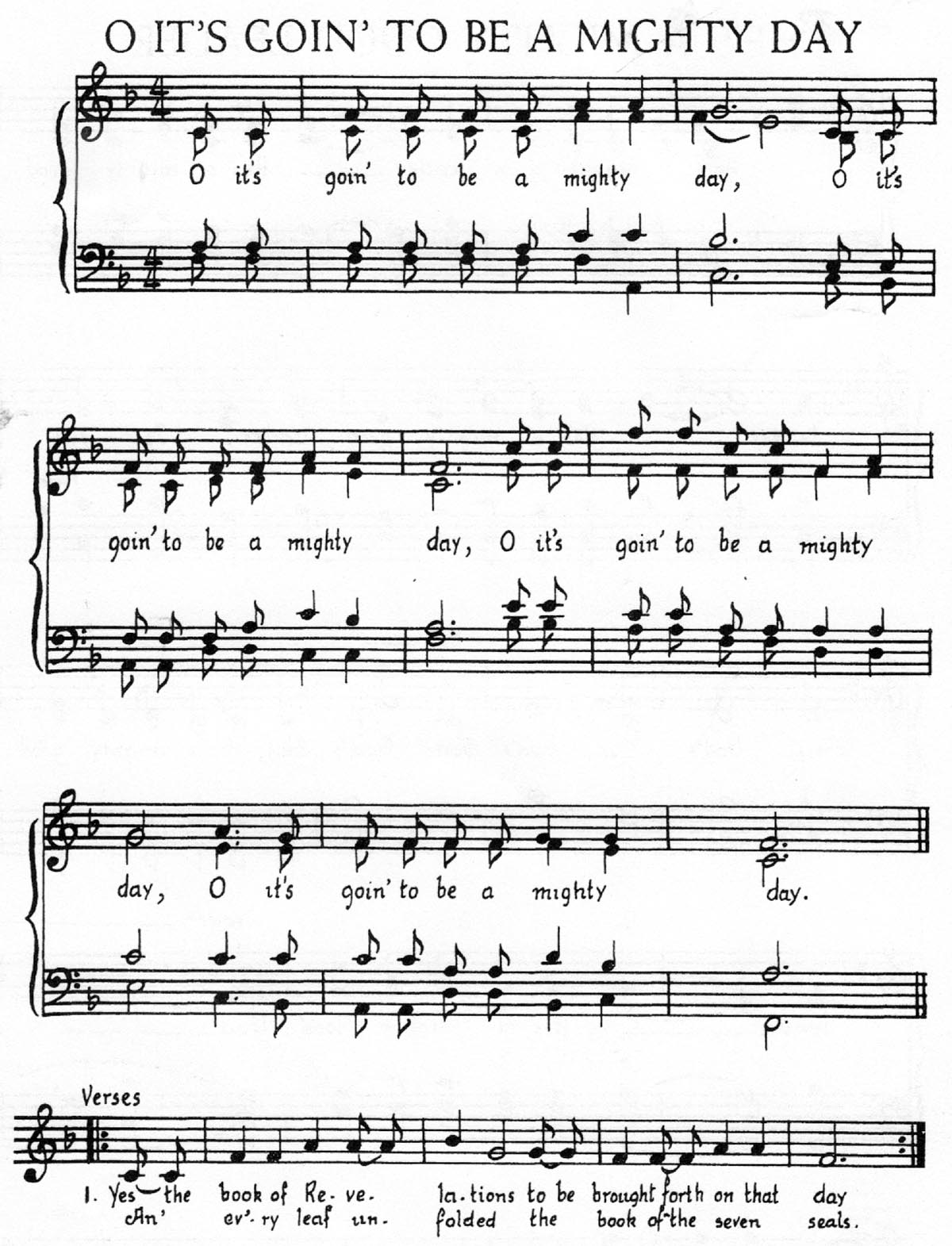

A gospel trio entertains the revelers, singing:

To the tune of “O It’s Goin’ to be a Mighty Day”: (Key of F)

Ganya, Lebedev and Prince Myshkin stand admiring Ayn.

The arrival of guests is announced.

Ayn Rand in the arms of John Galt.

Ganya, turning to Lebedev, inquires about the guests: “They are Nihilists, are they not?”

Lebedev, very excited: “No, they are not Nihilists, this is another lot — a special group, according to my nephew they are more advanced even than the Nihilists.” (turning to Prince Myshkin) “You are quite wrong, excellency, if you think that your presence will intimidate them; nothing intimidates them. Educated men, learned men even, are to be found among Nihilists; these go further, in that they are men of action. The movement is, properly speaking, a derivative from Nihilism — though they are only known indirectly, and by hearsay, for they never advertise their doings in the papers. They go straight to the point. For them, it is not a question of showing that Pushkin is stupid, or that Russia must be torn in pieces. No; but if they have a great desire for anything, they believe they have a right to get it even at the cost of the lives, say, of eight persons. They are checked by no obstacles. In fact, Prince, I should not advise you…”

Despite the warning, Prince Myshkin rises, and makes his way to open the door for his visitors. Ragnar Danneskjöld, Francisco d’Anconia and John Galt come in together. A joyous reunion ensues, as Ayn calls out their names in turn, as they embrace. They call her ‘Dagny’; she does not object.

Johnnie Dawes: “Do you know I am specially glad that today is your birthday!”

Prince Myshkin: “Why?”

Johnnie Dawes: “You’ll soon see. D’you know I had a feeling that there would be a lot of people here tonight? It’s not the first time that my presentiments have been fulfilled. I wish I had known it was your birthday, I’d have brought you a present — perhaps I have got a present for you! Who knows? Ha, ha! How long is it now before daylight?”

Someone, looking at his watch: “Not a couple of hours.”

Someone else: “What’s the good of daylight now? One can read all night in the open air without it.”

Johnnie Dawes: “The good of it! Well, I want just to see a ray of the sun. Can one drink to the sun’s health, do you think, Prince?”

Prince Myshkin: “Oh, I dare say one can; but you had better be calm and lie down.”

“They are Nihilists, are they not?”

Johnnie Dawes: “You are always preaching about resting; you are a regular nurse to me, Prince. As soon as the sun begins to resound in the sky — what poet said that? ‘The sun resounded in the sky.’ It is beautiful, though there’s no sense in it! — then we will go to bed. Lebedev, tell me, is the sun the source of life? What does the source, or spring, of life really mean in the Apocalypse? You have heard of the ‘Star that is called Wormwood’ Prince?”

Prince Myshkin: “I have heard that Lebedev explains it as the railroads that cover Europe like a net.”

Everybody laughs, and Lebedev gets up abruptly.

Lebedev, waving his hands to impose silence: “No! Allow me, that is not what we are discussing! Allow me! With these gentlemen… all these gentlemen…”

Lebedev, suddenly addressing Prince Myshkin: “On certain points… that is…”

(thumps the table repeatedly, laughter all around).

Lebedev, evincing a supreme contempt for his opponents: “It is not right! Half an hour ago, Prince, it was agreed among us that no one should interrupt, no one should laugh, that each person was to express his thoughts freely; and then at the end, when everyone had spoken, objections might be made, even by the atheists. We chose Mr. Thompson as president. Now without some such rule and order, anyone might be shouted down, even in the loftiest and most profound thought…”

Someone: “Go on! Go on! Nobody is going to interrupt you!”

Someone else: “Speak, but keep to the point!”

Another: “What is this star?”

Mr. Thompson, with much gravity: “I have no idea.”

Wesley Mouch, a little drunk: “I love these arguments, Prince, scientific and political.”

Wesley Mouch, turning suddenly towards Bertram Scudder: “Do you know, I simply adore reading the accounts of the debates in the English parliament. Not that the discussions themselves interest me; I am not a politician, you know; but it delights me to see how they address each other ‘the noble lord who agrees with me,’ ‘my honourable opponent who astonished Europe with his proposal,’ ‘the noble viscount sitting opposite’ — all these expressions, all this parliamentarianism of a free people, has an enormous attraction for me. It fascinates me, Prince. I have always been an artist in the depths of my soul, I assure you.”

Bertram Scudder, in high spirits, his gaiety was mingled with triumph, only meaning to egg him on, but he grows excited himself at the same time: “Do you mean to say, do you mean to say that railways are accursed inventions, that they are a source of ruin to humanity, a poison poured upon the earth to corrupt the springs of life?” Lebedev, with a mixture of violent anger and extreme enjoyment: “Not the railways, oh dear, no! Considered alone, the railways will not pollute the springs of life, but as a whole they are accursed. The whole tendency of our latest centuries, in its scientific and materialistic aspect, is most probably accursed.”

Bertram Scudder: “Is it certainly accursed? Or do you only mean it might be? That is an important point!”

Lebedev, vehemently: “It is accursed, certainly accursed!”

Someone, smiling: “Don’t go so fast, Lebedev; you are much milder in the morning.”

Lebedev, earnestly: “But, on the other hand, more frank in the evening! In the evening sincere and frank, more candid, more exact, more honest, more honourable, and… although I may show you my weak side, I challenge you all; you atheists, for instance! How are you going to save the world? How find a straight road of progress, you men of science, of industry, of cooperation, of trade unions, and all the rest? How are you going to save it, I say? By what? By credit? What is credit? To what will credit lead you?”

Bertram Scudder: “You are too inquisitive.”

Lebedev: “Well, anyone who does not interest himself in questions such as this is, in my opinion, a mere fashionable dummy.”

Bertram Scudder: “But it will lead at least to solidarity, and balance of interests, you will reach that with nothing to help you but credit? Without recourse to any moral principle, having for your foundation only individual selfishness, and the satisfaction of material desires? Universal peace, and the happiness of mankind as a whole, being the result! Is it really so that I may understand you, sir?”

Bertram Scudder, now thoroughly roused: “But the universal necessity of living, of drinking, of eating — in short, the whole scientific conviction that this necessity can only be satisfied by universal cooperation and the solidarity of interests — is, it seems to me, a strong enough idea to serve as a basis, so to speak, and a spring of life for humanity in future centuries.”

Lebedev: “The necessity of eating and drinking, that is to say, solely the instinct of self-preservation… Is not that enough? The instinct of self-preservation is the normal law of humanity…”

Bertram Scudder, breaking in: “Who told you that?”

Lebedev: “It is a law, doubtless, but a law neither more nor less normal than that of destruction, even self-destruction. Is it possible that the whole normal law of humanity is contained in this sentiment of self-preservation?”

Johnnie Dawes, turning towards Bertram Scudder and looking at him with a queer sort of curiosity: “Ah!”

Then seeing that Bertram Scutter was laughing, he began to laugh himself, nudged Eddie, who was sitting beside him, with his elbow.

Johnnie Dawes, again, cries out: “What time is it!”

He pulls Eddie’s silver watch out of his hand, and looks at it eagerly. Then, as if he had forgotten everything, he stretches himself out on the sofa, put his hands behind his head, and looked up at the sky. After a moment he gets up and comes back to the table to listen to Lebedev’s outpourings, as the latter passionately comments on Bertram Scudder’s paradox.

Bertram Scudder: “That is an artful and traitorous idea. A smart notion, thrown out as an apple of discord. But it is just. You are a scoffer, a man of the world, a cavalry officer, and, though not without brains, you do not realize how profound is your thought, nor how true. Yes, the laws of self-preservation and of self-destruction are equally powerful in this world. The Devil will hold his empire over humanity until a limit of time which is still unknown.”

Lebedev: “You laugh? You do not believe in the Devil? Scepticism as to the Devil is a French idea, and it is also a frivolous one. Do you know who the Devil is? Do you know his name? Although you don’t know his name you make a mockery of his form, following the example of Voltaire. You sneer at his hoofs, at his tail, at his horns — all of them the product of your imagination! In reality the Devil is a great and terrible spirit, with neither hoofs, nor tail, nor horns; it is you who have endowed him with these attributes! But… he is not the question just now!”

Johnnie Dawes, laughing hysterically: “How do you know he is not the question now?”

Lebedev: “Another excellent idea, and worth considering!”

Bertram Scudder: “But, again, that is not the question. The question at this moment is whether we have not weakened the springs of life by the extension…”

Ayn, eagerly: “Of railways?”

Lebedev: “Not railways, properly speaking, presumptuous youth, but the general tendency of which railways may be considered as the outward expression and symbol. We hurry and push and hustle, for the good of humanity! ‘The world is becoming too noisy, too commercial!’ groans some solitary thinker. ‘Undoubtedly it is, but the noise of wagons bearing bread to starving humanity is of more value than tranquillity of soul,’ replies another triumphantly, and passes on with an air of pride. As for me, I don’t believe in these wagons bringing bread to humanity. For, founded on no moral principle, these may well, even in the act of carrying bread to humanity, coldly exclude a considerable portion of humanity from enjoying it; that has been seen more than once.”

Eddie willers: “What, these wagons may coldly exclude?”

Ayn, shrugs: “If civilization is to survive, it is the morality of altruism that men have to reject.”

Lebedev, not deigning to notice the interruption: “That has been seen already. Malthus was a friend of humanity, but, with ill-founded moral principles, the friend of humanity is the devourer of humanity, without mentioning his pride; for, touch the vanity of one of these numberless philanthropists, and to avenge his self-esteem, he will be ready at once to set fire to the whole globe; and to tell the truth, we are all more or less like that. I, perhaps, might be the first to set a light to the fuel, and then run away. But, again, I must repeat, that is not the question.”

Someone: “What is it then, for goodness’ sake?”

Someone else: “He is boring us!”

Lebedev: “The question is connected with the following anecdote of past times; for I am obliged to relate a story. In our times, and in our country, which I hope you love as much as I do, for as far as I am concerned, I am ready to shed the last drop of my blood…”

All: “Go on! Go on!”

Lebedev: “In our dear country, as indeed in the whole of Europe, a famine visits humanity about four times a century, as far as I can remember; once in every twenty-five years. I won’t swear to this being the exact figure, but anyhow they have become comparatively rare.”

Bertram Scudder, sarcastically: “Comparatively to what?”

Lebedev: “To the twelfth century, and those immediately preceding and following it. We are told by historians that widespread famines occurred in those days every two or three years, and such was the condition of things that men actually had recourse to cannibalism, in secret, of course. One of these cannibals, who had reached a good age, declared of his own free will that during the course of his long and miserable life he had personally killed and eaten, in the most profound secrecy, sixty monks, not to mention several children; the number of the latter he thought was about six, an insignificant total when compared with the enormous mass of ecclesiastics consumed by him. As to adults, laymen that is to say, he had never touched them.”

A general outcry.

Mr. Thompson: “That’s impossible! I am often discussing subjects of this nature with him, gentlemen, but for the most part he talks nonsense enough to make one deaf: this story has no pretence of being true.”

Lebedev: “Remember the siege of Kars! And you, gentlemen, I assure you my anecdote is the naked truth. I may remark that reality, although it is governed by invariable law, has at times a resemblance to falsehood. In fact, the truer a thing is the less true it sounds.”

Someone, scoffing in objection: “But could anyone possibly eat sixty monks?”

Lebedev: “It is quite clear that he did not eat them all at once, but in a space of fifteen or twenty years: from that point of view the thing is comprehensible and natural…”

Bertram Scudder: “Natural?”

Lebedev, with pedantic obstinacy: “And natural.”

Lebedev: “Besides, a Catholic monk is by nature excessively curious; it would be quite easy therefore to entice him into a wood, or some secret place, on false pretences, and there to deal with him as said. But I do not dispute in the least that the number of persons consumed appears to denote a spice of greediness.”

Prince Myshkin has been listening in silence up to that moment without taking part in the conversation, but laughing heartily with the others from time to time. Evidently he is delighted to see that everybody was amused, that everybody is talking at once, and even that everybody is drinking.

Prince Myshkin, quietly: “It is perhaps true, gentlemen.”

Prince Myshkin, seeming as if he were not intending to speak more, suddenly, in such a serious voice that everyone looks at him with interest: “It is true that there were frequent famines at that time, gentlemen. I have often heard of them, though I do not know much history. But it seems to me that it must have been so. When I was in Switzerland I used to look with astonishment at the many ruins of feudal castles perched on the top of steep and rocky heights, half a mile at least above sea-level, so that to reach them one had to climb many miles of stony tracks. A castle, as you know, is, a kind of mountain of stones — a dreadful, almost an impossible, labour! Doubtless the builders were all poor men, vassals, and had to pay heavy taxes, and to keep up the priesthood. How, then, could they provide for themselves, and when had they time to plough and sow their fields? The greater number must, literally, have died of starvation. I have sometimes asked myself how it was that these communities were not utterly swept off the face of the earth, and how they could possibly survive. Lebedev is not mistaken, in my opinion, when he says that there were cannibals in those days, perhaps in considerable numbers; but I do not understand why he should have dragged in the monks, nor what he means by that.”

Bertram Scudder: “It is undoubtedly because, in the twelfth century, monks were the only people one could eat; they were the fat, among many lean!”

Lebedev, triumphantly: “A brilliant idea, and most true! For he never even touched the laity. Sixty monks, and not a single layman! It is a terrible idea, but it is historic, it is statistic; it is indeed one of those facts which enables an intelligent historian to reconstruct the physiognomy of a special epoch, for it brings out this further point with mathematical accuracy, that the clergy were in those days sixty times richer and more flourishing than the rest of humanity. And perhaps sixty times fatter also…”

Mr. Thompson, amid laughter: “You are exaggerating, you are exaggerating, Lebedev!”

Prince Myshkin, speaking so seriously that his tone contrasts quite comically with that of the others: “I admit that it is an historic thought, but what is your conclusion?”

The others are very nearly laughing at him, too, but he does not notice it.

“My conclusions are vast!”

Someone, whispering in Prince Myshkin’s ear: “Don’t you see he is a lunatic, Prince? Someone told me just now that he is a bit touched on the subject of lawyers, that he has a mania for making speeches and intends to pass the examinations. I am expecting a splendid burlesque now.”

Lebedev, in a voice like thunder: “My conclusion is vast!”

Lebedev: “Let us examine first the psychological and legal position of the criminal. We see that in spite of the difficulty of finding other food, the accused, or, as we may say, my client, has often during his peculiar life exhibited signs of repentance, and of wishing to give up this clerical diet. Incontrovertible facts prove this assertion. He has eaten five or six children, a relatively insignificant number, no doubt, but remarkable enough from another point of view. It is manifest that, pricked by remorse — for my client is religious, in his way, and has a conscience, as I shall prove later — and desiring to extenuate his sin as far as possible, he has tried six times at least to substitute lay nourishment for clerical. That this was merely an experiment we can hardly doubt: for if it had been only a question of gastronomic variety, six would have been too few; why only six? Why not thirty?

But if we regard it as an experiment, inspired by the fear of committing new sacrilege, then this number six becomes intelligible. Six attempts to calm his remorse, and the pricking of his conscience, would amply suffice, for these attempts could scarcely have been happy ones. In my humble opinion, a child is too small; I should say, not sufficient; which would result in four or five times more lay children than monks being required in a given time. The sin, lessened on the one hand, would therefore be increased on the other, in quantity, not in quality. Please understand, gentlemen, that in reasoning thus, I am taking the point of view which might have been taken by a criminal of the middle ages. As for myself, a man of our present times, I, of course, should reason differently; I say so plainly, and therefore you need not jeer at me nor mock me, gentlemen.” (addressing Mr. Thompson) “As for you, Mr President, it is still more unbecoming on your part.” (turning back to the others) “In the second place, and giving my own personal opinion, a child’s flesh is not a satisfying diet; it is too insipid, too sweet; and the criminal, in making these experiments, could have satisfied neither his conscience nor his appetite. I am about to conclude, gentlemen;

And my conclusion contains a reply to one of the most important questions of that day and of our own! This criminal ended at last by denouncing himself to the clergy, and giving himself up to justice. We cannot but ask, remembering the penal system of that day, and the tortures that awaited him — the wheel, the stake, the fire! — We cannot but ask, I repeat, what induced him to accuse himself of this crime? Why did he not simply stop short at the number sixty, and keep his secret until his last breath? Why could he not simply leave the monks alone, and go into the desert to repent? Or why not become a monk himself? That is where the puzzle comes in! There must have been something stronger than the stake or the fire, or even than the habits of twenty years! There must have been an idea more powerful than all the calamities and sorrows of this world, famine or torture, leprosy or plague — an idea which entered into the heart, directed and enlarged the springs of life, and made even that hell supportable to humanity! Show me a force, a power like that, in this our century of vices and railways! I might say, perhaps, in our century of steamboats and railways, but I repeat in our century of vices and railways, because I am drunk but truthful! Show me a single idea which unites men nowadays with half the strength that it had in those centuries, and dare to maintain that the springs of life have not been polluted and weakened beneath this star, beneath this network in which men are entangled! Don’t talk to me about your prosperity, your riches, the rarity of famine, the rapidity of the means of transport! There is more of riches, but less of force. The idea uniting heart and soul to heart and soul exists no more!”

Ayn, John Galt, Francisco d’Anconia and Ragnar Danneskjöld step forward and recite in solemn, triumphant unity:

“I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine!”

An angelic chorus answers the Galtian Oath…

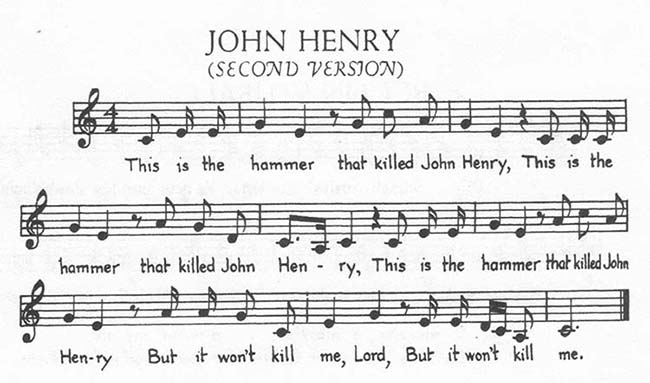

Chorus: “John Henry” (Key of C)

- This is the hammer that killed John Henry

- This is the hammer that killed John Henry,

- This is the hammer that killed John Henry,

- But it won’t kill me, Lord, but it won’t kill me.

To the tune of “John Henry”: (Key of C)

Transition to Eddie Willers’ living room…