Atilla Shrugged

Foreword

The Genius of Ayn Rand

by Nicoli Gogel

When The Fountainhead became fashionable among the architectural set, Ayn Rand was not pleased. When the readers of the New York Times were advised that it was an interesting novel about architecture, she was offended and outraged; evidently the reviewer identified with Ellsworth Toohey. Whatever his motives, certainly we can conclude that the central theme of The Fountainhead is something decidedly more than the raising of roofs.

I am sympathetic with Ms. Rand on this account, because I still burn with indignation when I remember how “The Overcoat” became a sort of cult classic among tailors. I was expecting that I would finally get some recognition and respect from the critics; instead, all I got was some overstuffed personage calling on me about an honorary membership in the Moscow tailor’s guild. Needless to say, I threw him out and spoke with no one for a week, I was so angry. I can only imagine how Ayn felt, so you may appreciate the extent to which I sympathize with the million ways in which her work has been misunderstood. An ordinary writer will anguish over the blankness of the paper before them, scouring his brain for some notion that might impress itself upon the mind of the reader as so entirely uncommon as to be astonishing, whereas Ayn possessed a genius which surpassed that great ocean of mediocrity.

The thing that first impressed me about Ayn was her mastery of ideas that a less audacious author might have rejected as thread-worn; too shabby to provide protection against the cruel winter winds, which, (according to St. Petersburg custom), blowing from all four directions at once, leave one scampering for the shelter of the nearest doorway, and so, perhaps, to fall into bad company. The mediocre author will naturally shy away from such risks, and cleave to more reliably popular themes.

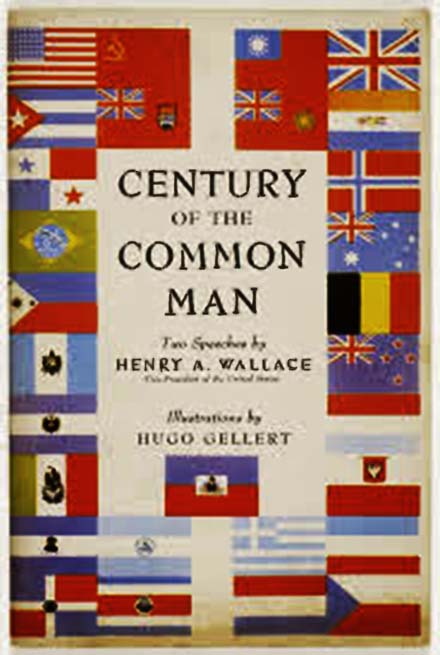

In contrast, Ayn started with little more than an old cloak made on an Aristotelian loom from the golden days of Feudalism, which, having been worn by the aristocracy all the way through the Enlightenment, the Industrial Age and on into our own Century of the Common Man, was as threadbare as the old overcoat of Akaky Akakievich.

This is the genius of Rand: that she was able to weave a renewed fabric from these seemingly spent scraps, so magnificent, so heroic, that it has become the foundation of an untrodden faith that seeks no lower object than to turn back Abraham and his Prophets, the Talmud and the New Testament, all in a throw.

Speaking as a writer who has spent many an afternoon, my chin planted in my palms, gazing into the lamp light of eternity, I can only express a sort of awesome admiration.

— Nikolai Gogol Sorochyntsi, Ukraine